The true inventor of Bazball was born 150 years ago, and his records are still utterly bonkers

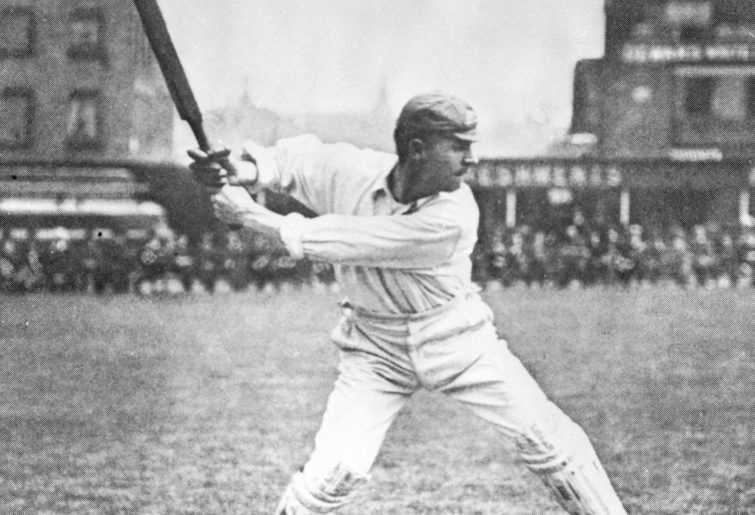

“No cricketer that has ever lived hit the ball so often, so fast and with such a bewildering variety of strokes.” – HS Altham

Gilbert Jessop was born 150 years ago this week, on 19 May 1874. On the eve of a T20 World Cup, it’s timely to acknowledge him as the fastest run-scorer of all time.

As a cricketer, he was unique, just like WG Grace, SF Barnes, Victor Trumper and Don Bradman. Rather than doing what others did, but slightly better, he instead he did what no-one else could.

A Test-winning century in 75 minutes. 53 first-class centuries, made at an average rate of 83 runs per hour. Five double-centuries, despite batting for three hours only once in his 21-year career. All without ever playing a limited-overs game. Or attempting a ramp, scoop, switch-hit or reverse-sweep.

He was also a superb fieldsman who once ran out 30 batsmen in a single season, and a fast bowler good enough to debut for England in that role. Today he’d be a genuine white-ball triple-threat, and T20 franchises would be clamouring for his signature. Even if conservative Test selectors didn’t consider him sufficiently orthodox and predictable to always be one of the first players picked.

The style

“Jessop had an assortment of strokes to deal with anything the bowler could send down. A fast ball on the off might be swept to the fine leg boundary; a nagging delivery on the leg stump cut savagely through the slips; a length ball on the middle stump could be cut, pulled or lofted over the bowler’s head, according to the placing of the field or the incalculable whim of the moment.” – Rowland Ryder

Jessop was nicknamed “The Croucher,” due to his low batting stance. While only 11 stone (70kg) in weight, and 5 foot 7 inches tall, he was extremely light on his feet, and immensely strong. His slight build was an advantage, just as it would prove to be for Don Bradman, Sachin Tendulkar and Brian Lara.

He wielded a heavy bat with hands spread far apart, and regularly advanced down the pitch or played from deep within the crease. As a result, he was able to effectively drive, cut, hook, late-cut and leg-glance. And from the commencement of every innings, he hit hard and often, without ever slogging.

“Jessop’s match,” The Oval, 1902

This Ashes series’ fifth Test is one of the greatest games of all time. Jessop’s performance turned certain defeat for England into a thrilling victory.

After Australia had scored 324 on a dry pitch, heavy overnight rain restricted the home side to 183 on a wet one. When the visitors batted again, Jessop ran out the immortal Victor Trumper by intercepting a drive, and rifling a throw to Dick Lilley before the batsman could regain his ground. England skipper Archie MacLaren described it as the match’s turning point. On a still-soft pitch, Australia could total only 121.

(Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The home side now required 263 runs for victory on a pitch that had deteriorated further following yet another night of rain. With its innings in ruins at 5/48, Jessop joined FS Jackson in a partnership that changed the game’s course. In 65 minutes they added 109 runs, of which Jessop’s share was 83. He then added a further 30 runs in ten minutes with George Hirst, who contributed a mere nine.

In the space of 77 minutes, Jessop scored 104 runs from 80 deliveries. His last 29 runs took him 14 deliveries. He struck 16 fours and a five, at one point hitting Jack Saunders for four consecutive boundaries.

Two of Jessop’s drives landed on a pavilion roof, and a third on a changeroom balcony. Remarkably, none of them counted as sixes, which at the time needed to be hit completely out of a ground rather than simply over a boundary. Two of those strokes advanced his score from 88 to 96, rather than to 100 as would be the case today. Future Test captain CB Fry described the innings:

“Sometimes he would chase five yards down the pitch to wang the ball mountain-high towards Vauxhall. Sometimes he pretended to chase but, lancing back, caught it short and punched it terrifically, square past point towards the gasometer. The fieldsmen gradually became dotted round the horizon. But it was Jessop’s hour and he bisected them all. On and on he thrashed his way, a hurricane of batsmanship.”

Jessop’s knock enabled England to win a thrilling contest by the narrowest of margins, with last-wicket pair Hirst and Wilfred Rhodes sharing an undefeated 15-run partnership.

In the same series’ earlier match at Sheffield, he had volunteered to open the innings and scored 55 runs from 48 deliveries. Another notable Test innings took place against South Africa at Lord’s in 1907 and enabled the home side to recover from 5/158 to 428. He contributed 93 runs from 63 deliveries in 75 minutes, including 14 fours and a six, before being caught beside the sightscreen.

The career

“He was undoubtedly the most consistently fast scorer I have seen. He was a big hitter, too, and it was difficult to bowl a ball from which he could not score. He made me glad that I was not a bowler. Gilbert Jessop certainly drew the crowds, too, even more than Bradman, I should say.” – Jack Hobbs

Jessop’s performance at The Oval in 1902 was no flash in the pan. Uniquely among batsmen whose strategy was immediate and relentless aggression, he made substantial scores regularly.

Across a 21-year career, he top-scored for his side once in every four innings, and reached the half-century mark better than once in every five innings. He amassed 1,000 runs in an English summer 14 times. His season aggregates included 2,210 runs in 1900, and 2,323 in 1901. He scored a pair of centuries in the same match on four occasions. And of his 53 centuries, 16 were in excess of 150 runs.

However, what differentiates Jessop is his scoring rate. His capacity to turn a game in literally minutes was a constant threat to opponents and made him his era’s greatest drawcard.

In 840 innings, he batted for three hours just once, and for two hours only ten times. And on the 180 occasions that he reached the 50-run mark, he averaged 79 runs per hour, and scored at slower than a run-a-minute just 27 times.

For his 53 centuries, his average scoring rate increased to 83 runs per hour, and his average time for reaching the 100-mark was 72 minutes. He scored a century in less than an hour on 12 occasions. The slowest century that he ever scored took him just two hours. And unsurprisingly, he contributed 72 per cent of all runs scored in total while he was at the crease.

Confirming his class, he scored more runs and centuries, and took more wickets, against the might of Yorkshire than any other opponent. His performances against them included:

– 101 in 40 minutes, out of 118 runs scored, at Harrogate in 1897.

– 104 and 139 at Bradford in 1900, with each of the centuries being scored before lunch on a separate day. In the process, he hit Rhodes completely out of the ground eight times for sixes, and over the boundary another eight times to earn merely fours.

-233 in 150 minutes with 33 fours, out of 318 runs scored, at Lord’s in 1901.

While he played too many other outstanding innings to list, here are five further highlights:

– 206 in 140 minutes with 27 fours, out of 315 runs scored, against Nottinghamshire in 1904.

– 200 in 130 minutes, on his way to 234 in 155 minutes with 40 fours, out of 346 runs scored, against Somerset in 1905.

English cricketer Gilbert L Jessop. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

– 286 in 170 minutes with 42 fours, out of 355 runs scored, and passing the 200 mark in two hours, against Sussex in 1903.

– 240 in 200 minutes with one six and 35 fours, out of 337 runs scored, against Sussex in 1907, the only time that he ever batted for three hours.

– a century in 42 minutes, before proceeding to 191 in 90 minutes with five sixes and 30 fours, out of 234 runs scored, against The Players in 1907.

The all-rounder

Jessop was more than just a batsman. In 493 first-class games, he scored 26,698 runs at 32.63 but also claimed 873 wickets at 22.79 and took 463 catches.

He debuted for England as an opening bowler against Australia at Lord’s in 1899, taking 3/105 from 37.1 overs. In the same game, he scored 51 runs in 62 minutes with nine boundaries, from number eight in the batting order. And at the SCG in 1901/02, he claimed his best Test figures of 4/68.

In England in 1897, in addition to scoring 1,219 runs, he also took 116 wickets and finished tenth in the national bowling averages. And in 1900, he scored 2,210 runs and claimed 104 wickets, becoming only the third player to attain that double.

In addition, his fielding at cover-point was superb. He was quick to the ball with safe hands, and had a fast and accurate throw. Having closely studied baseballers during two tours to America, he subsequently threw out 30 batsmen in a single English season. MacLaren wanted him to play against Australia whenever possible, because of the ever-present threat he posed of running out a star opponent.

His all-round sporting abilities extended well beyond the cricket field. He also excelled in hockey, football, rugby, billiards and golf, and ran 100 yards in 10.2 seconds.

What might have been

“We have never before produced a batsman of quite the same stamp. We have had harder hitters, but perhaps never one who could in twenty minutes or half an hour, so entirely change the fortunes of the game.” – Wisden Cricketers’ Almanack

In Test matches, Jessop scored 569 runs at a rate of 112 per 100 balls faced. That rate has never been even remotely approached by any other batsman.

However, his raw figures could have been far more impressive. Between his Test debut in 1899, and the outbreak of WWI in 1914, he played just 13 of a possible 28 matches at home, and five of England’s 35 games in Australia and South Africa.

He suffered severely from sea sickness during voyages to and from America in 1897 and 1899, and then Australia in 1901/02. As a result, he declined six subsequent tours to Australia or South Africa. For the last of those, to South Africa in 1913/14, he had been offered the team’s captaincy.

Playing as an amateur, to preserve his social status and his eligibility to captain Gloucestershire, sometimes restricted his availability. He instead spent parts of some summers, as well as each winter, engaged in other pursuits.

Finally, his scoring rate was limited by his era’s conditions. Uncovered pitches were often slow and unpredictable after rain. Bats were far less powerful than those of today. Protective headwear did not exist. Outfields were slower, and boundaries not shortened by ropes. And for most of his career, it was necessary to hit a ball completely out of a ground to score a six.

Admittedly some aspects of his era did work in his favour. Over-rates were approximately 50 per cent higher than they are in the modern era, enabling him to receive far more deliveries in a given period than he would nowadays. And the overall standard of fielding would not have been as high as it has since become.

Sports opinion delivered daily

It’s tempting to speculate how successful he might have been if born in 2000. First-class airline seats and five-star hotels would have addressed his travel sickness. While an avowed amateur, the rise of professionalism would have enabled him to play full-time and be handsomely paid. Railway-sleeper bats, highway-like pitches, helmets, slick outfields and smaller grounds, along with the modern focus on strength and conditioning, would have enhanced his capacity to score rapidly.